This is a story about the theft of one of my photographs that ended up in a copyright infringement lawsuit. It was an interesting journey that taught me a lot about the American legal system. It taught me something about the ethics of the photo industry. It also taught me perseverance and a solid belief in what’s right and what’s wrong pays off. Eventually.

It started with a photograph of wheelchair I made in Athens, Ohio in the spring of 1982. It was living on the back porch of a house I was living in at the time while attending graduate school at Ohio University. It was part of a series I was working on using a Widelux panoramic camera.

In the winter of 1984 I moved to Seattle, Washington to pursue a career in photography. To promote myself I created a series of calendars using several panoramic images. One of them was of the wheelchair. I later submitted the calendars to Communication Arts Magazine to be considered for publication. It was accepted and I was featured in the 1985 CA Photography Annual. I was very excited about receiving national exposure in such a prestigious magazine and hoped it would lead to bigger and better things. It did, just not how I expected.

In June of 1987, I received a phone call from the Wyse Advertising agency in Cleveland, Ohio requesting some general information. They had seen my image of the wheelchair in CA and loved it and talked about working with them to make an image of FDR’s wheelchair in Hyde Park, New York, for an ad they were proposing for General Dynamics. Was I interested? Sure, but I did think to myself, “Do they think I am the only one who can make a photograph of a wheelchair?”. And that was then end of the call.

Two or three days later they called again to request an estimate. I requested the specs, and a comp or layout of some kind to see what they were thinking. Comps were and maybe still are, the method by which designers sell their ideas to potential clients. A pitch as it were. They are often drawings or illustrations or photographs. While not legal, designers often just grab images from magazines or whatever source and slap them in their comps and run with it. They rarely, if ever, ask permission. And of course, never pay fees for comp use.

The next day the comp arrives with my image taking up half of the double page spread. I was a bit surprised they didn’t ask my permission, but felt it gave me the inside track to get the job. In fact, I thought I had the job, but assumed they would be getting other bids. I copied the comp for my records and returned it with my estimate.

I called to confirm safe arrival and was told everything was in good order, and my estimate looked good. The two other bids were considerably higher. I didn’t try to low ball the job, but I wanted the job, so my numbers were very conservative for the scope of the job. The other two photographers were from New York and more seasoned professionals. I was still young and new to the business. The Wyse person said they would get back to me soon. They didn’t.

Over a week later and after three phone calls I get thru only to be told I didn’t get the job. At that point it occurred to me that they never intended to hire me. The main reason was because they never asked to see my portfolio. They only wanted to use my photo for the comp and as I would later find out, there was a fourth photographer involved who eventually got the job.

So, I wrote a letter asking who got the job? What their bid and was I ever seriously considered for the job? No response.

Later in August I was in Washington, DC working on a project in Baltimore. I had spent time there in the spring making photographs for use as guest room art for a large hotel in the area. The designer, a friend of mine also asked to make architectural photos to document the finished hotel. Guest room art is low budget and the big art budgets are for art in the lobbies and restaurants and such. When we came to the main restaurant, there were three large paintings on the walls of this elegant space. One of them was an exact copy of one of my photographs. I was shocked and turned to my friend with a look of disbelief. He sheepishly shrugged his shoulders and said the guy wasn’t a very good with compositions, so he gave him one of my photos to paint. I was pissed and said he could have asked my permission first. I deserved some of the $5000 he paid that guy to copy my image. But I let it go. There was, and probably still is a fine line between standing up for your rights and rocking the boat and getting blacklisted.

A few days later I was reading the Washington Post and turned the page to see a full-page ad for General Dynamics prominently featuring his wheelchair. My first response was that’s my photo! My second response was no it was not, just a very, very good copy. My third response was shit; I have been screwed again. Fortunately, my fourth response was no, it doesn’t end here.

Back in Seattle, I call the Wyse agency several times. Left messages as why I was calling and everything. They didn’t return my calls. I decided to investigate my legal options.

Enough time has passed that I forget the exact order of things, but it went something like this. I contacted the ASMP legal guy. ASMP stands for American Society of Magazine Photographers (now Media Photographers) and is a national photographer trade organization I was a member of at the time. He turned me away; said I didn’t have a case. I contacted two legal eagles in New York City who did copyright work and had been featured in Photo District News, a prominent photo magazine at the time. They turned me away too, saying I didn’t have a case. Undeterred I connected with an attorney who was a friend of a photographer friend of mine. He agreed to write a letter to Wyse and rattle the saber and hopefully get them to open a dialog. I honestly felt that Wyse owed me something. They had already skipped the please and thank you part, so I felt they owed me a comp fee and reference fee for the use of my image. While part of the lexicon of the visual communications industry, no one actually paid such fees. Barrowing other creative’s work was more common and pretty much accepted. Wyse attorneys opened the dialog with a fuck off and die response. At that point my attorney said he could take it no further as he was not a copyright specialist but had a friend who was. He introduced me to Rex Stratton.

Side note. I stopped writing this piece about a month ago, thinking I would take it up the next day. The next morning, I thought, I wonder what Rex is up to these days. I had not spoken to him for several years. So, I Googled him and the first thing item that showed up was his obituary. He had passed away a few months ago. It took a little of the wind out of my sails, and it has taken me some time to recollect my thoughts and move on. You see, none of this would have happened without Rex.

Rex was a very nice guy who ran a small firm and would take his dog to work. He was very patient with me and always explained every step of the process. He made it feel like a game of chess, something that required strategy more than anything. He explained what intellectual property was and, what was and wasn’t protected by law. Thus, my education. He also gave me breaks on his billing. One of the first things we did was wait. There was a major copyright lawsuit going on at the time and he wanted to wait for the outcome. If it came down a certain way, he would be able to use it as a precedent in our case. So, we waited for about a year. I don’t recall the name of the case, but it did come out in our favor, so we moved on.

The first thing Rex tried to do was to get Wyse to settle out of court. But they were disagreeable and only reluctantly offered money that was not even enough to cover Rex’s fees. Rex explained their strategy was to drag it out and hope I would give up and go away. I didn’t. I really felt the need to know if they could get away with this. Eventually we had to file a lawsuit. And fees began to mount. Around this time the word was out in the Seattle photo community that I was involved in a lawsuit and the reviews were mixed. Most photographers questioned what I was doing, and I received very little support. Oddly enough, art directors and designers were more supportive. But everyone asked if I knew what I was doing? Could it backfire and I get blacklisted? I guess I felt if that was the case, I was in the wrong line of work. If the thief of one’s intellectual property was acceptable then I wanted no part of this industry. I even recall having this conversation with a photographer at some art opening. He thought what I was doing was wrong. In frustration, I said, well maybe I will just go back to being an art director and steal your work. He looked at me puzzled and said, you would do that? I said why not, you’re telling me its ok.

The process dragged on and on. Letters back and forth, filings back and forth. All in a language foreign to me. We even had an arbitration. I recall about seven or eight of us sitting around a conference room table with a mediator leading the show. Wyse/General Dynamics had 3 or 4 lawyers at the table. I recall a lot of posturing and bantering about legal stuff, but no discussion about what I feel the real issue was. There was no discussion about my photograph and how it was used and copied without my permission. There was my photograph and their ad laying on the table. And no one seemed to notice. In frustration I speak out and ask what’s wrong with you people? All this talk about nothing and what a huge waste of time… Rex kicks me under the table. He would later explain during a break that I had shown weakness. That I had no stomach for litigation. So, he suggested we try to settle. After the break, Rex offered to settle for $35k. $25k for his fees and $10k to me. I distinctly recall what happened next. The slimy lawyer from New Jersey representing General Dynamics looked at me, sneered and shook his head. He stood up and looked at Rex and said I’ll see you in court. And left the room. No discussion, no nothing. He all but dared us to take it to the next level. Drag it out more, he’ll go away.

More legal fees, more time as Rex prepared for trial. Because General Dynamics did work in the State of Washington, we could have the trial here in Seattle and make them come to us. One of the things Rex asked me to do was to help find an expert witness to speak on my behalf. A photographer with a national reputation. One who could speak to the benefits of having done national ad work and what it can do for one’s career and how I was denied that. I reached out to 3 prominent Seattle photographers, all veterans of the business with loads of experience in national ad campaigns. I phone one of them 6 times, leaving a message each time with his studio manager. No response. Same with the second guy. I called the third guy several times, leaving messages on his machine, until one call he finally answered. He hammered me. He said he had spoken to the first photographer about me and neither of them wanted anything to do with me, that what I was doing was wrong. And he hung up. I later ran into him at an art opening, and he hammered me again, in public. This time he was more vocal and opinionated. Not only what I was doing was wrong, but that I was biting the hand that feeds us, that my attorney was a shyster, that I was pinning corporate America to the wall and pick pocketing them. This coming from a man whose big corporate client was Marlboro, the cigarette guys. He shot one of the Marlboro Men. And not so quietly gave 10% of his fees to the American Cancer Society. And he’s lecturing me on ethics? None the less, it was all troubling to me. I felt alone in my quest, except for the support of my rep and other friends. I so I soldiered on.

We decided to go in a new direction. Instead of a photographer as expert witness, I was to find someone who could speak about the art of photography and not the business of photography. I knew just the right guy. Rod Slemmons. Rod was at the time Curator of Prints at the Seattle Art Museum. He was quite knowledgeable in the history of photography and could speak to the art of photography and address the similar aspects of my photograph and the infringing one used in the ad. As I came to understand, in copyright law, you must prove two things.

According to Google:

To prove copyright infringement, the plaintiff must show (1) that the defendant had access to the plaintiff’s work and (2) that the defendant’s work is substantially similar to protected aspects of the plaintiff’s work.

Access was easy to prove. They saw my image in CA Magazine and copied it and so on. Once you prove that, proving substantial similarity becomes much easier.

Finally, after three years we had our two days in court in the spring of 1990. It was a bench trial. No jury, so only the judge to determine the outcome. Much of the next two days are lost in my memory as it was just so legal posturing and proceedings foreign to me. For instance, the first thing their attorney did was file for dismissal. That shocked me, thinking we were over before we even got started. Rex told me to relax, it was something they had to do. The judge would deny it. He did. Rex carefully laid to me what would happen. We would do this, they would do that and then we do this, etc. A chess match. Rex was extremely confident about the whole thing. He knew his stuff and their attorney was general counsel and not fluent in intellectual property law. Just another example of them not taking our case seriously.

One of the interesting things that Rex did to admit as evidence was to enlarge both photographs to 40×30” and mount them of foam core to display in the courtroom during the proceedings and in full view of the judge. When their attorney spoke, she took them down. When Rex spoke, he put them back up. Back and forth they went A chess match.

Then there was the parade of witnesses. For their part Rex called upon their photographer, the art director from the Wyse agency and a marketing guy from General Dynamics. All were very business-like. All admitted to seeing the comp with my photo in it. All admitted to having the comp on the photo shoot at Hyde Park. And all vehemently denied having the comp on hand for photo reference. They denied any similarity and in no way did they copy my image. The merely had the comp on to refer to the text. Really? They slowly began to paint themselves in a corner.

For our part, there were three witnesses. Myself, Rod and a friend who was quite familiar with my photography. He and I had both gone to Ohio University and upon meeting him in Seattle years later, and seeing my portfolio, he would recognize the exact location of that image, which blew me away at the time. He also was aware it got an award from CA Magazine and knew I was up for a job based on the image. And he happened to own a copy of the print as well. When the ad first came out and he saw it in Time Magazine, he called me up to congratulate me for the fine job I did and having national exposure. I told him it wasn’t my work. So, Rex wanted his story. Under cross examination, he became monetarily and genuinely confused as to which of the two large images was mine. That may seem like a blunder, but in fact, added fuel to the fire. The images were obviously enough alike to cause confusion.

I was up next. Rex had coached me at length as to what to say and what not to say and in general what to expect from cross examination and how to respond. He knew I could speak passionately about my work, but there were questions he couldn’t ask. He couldn’t lead the witness. I couldn’t say they stole my idea, as ideas are not protected by copyright law. But I could say they stole my expression, they stole my composition, they stole the spirt and soul of my work and so on and so forth. So Rex says when he asks a particular question, that would my cue to go off on an emotional rant. He also said that at some point the opposing attorney would object and the judge would give me a polite wrist slapping and ask me to stop rambling and be succinct. They did, but by that time my impassioned words would have made a point with the judge. I don’t recall being cross examined, probably because by that time they knew they were skating on thin ice.

Last up was Rod. Being an academic, he spoke very eloquently and with authority. He spoke to the symbolism of the various elements of the images, the balustrade, the light, the wheelchair itself. He spoke to the identical perspective of the images and how looking up elevated the importance of the chair, looking up at the person who would inhabit the chair. He articulated all things I felt and put into the photograph but hadn’t able to put into words. It was like listening to an art history lecture at the Museum. I just kept thinking as I sat there, yea Rod, you go, you are spot on. And then he did something brilliant. He took a piece of tracing paper and laid it over the enlarged print of my image. He then traced the basic compositional elements. He traced the exact perspective, a basic line drawing. He then lifted the tracing paper and laid it over the photo from the ad. The lines matched perfectly. He left little doubt that the ad photo was a copy of mine. That was the last nail in the coffin.

The defense then went about doing other actions in an attempt to minimize the damage. They claimed they didn’t copy my full image, since the original was a panoramic and they cropped it. Therefore, they had created something new and possibly fall under Fair Use, a clause in copyright law that permits people to “barrow” intellectual property under certain circumstances. They even said that they photo was only a small part of the ad. That the copy and layout were considerably more important than the photo. They even claimed the photo was only worth 20% of the ad. When I asked Rex what they were doing, he said they were posturing for when they lose, they would only have to pay 20% of the award. I don’t think the judge bought it, but at that point the defense was grasping at straws.

And then the trial was over, and we waited for the judge to make a decision, which would take another three months or so. When I started this process, I wanted them to admit their guilt and apologize. And compensate me in some way. I learned thru it all that I would never get a guilty admission or an apology from Wyse or General Dynamics. As that could potentially open the flood gates to other lawsuits. And it would be a sign of weakness on their part. Instead, they would pay you more money just to go away.

The judge would later rule in our favor and award us $150,000. With $60 to me and $90k for legal fees. Wyse decided to appeal. Rex was happy to go another round, as he was confident of victory and if they appealed again, he could argue the case before the Supreme Court. I wanted it over. We had won after all. We had set a precedent.

Curtis v. General Dynamics had a nice ring to it. But we weren’t done yet. In an effort to lighten the load of the courts, another round of mediation was arranged. Same characters as before, complete with the slimy attorney from New Jersey. We had a different mediator and this time, after some discussions, she separated us into two different conference rooms and went back and forth between the two waring parties. She spoke with them first. I recall she was a pleasant woman. She was smart and easy to talk to. When she came to us, she basically said she was on our side. But Wyse had backed themselves into a corner and had egg on their face. And it was up to me to throw them a bone. Would I take $125k instead? Knowing we could end this I looked at Rex and asked what he thought? I asked him if we stood to gain anything more than additional money. We had won. We could easily lose the next round and be back to square one. Was there good reason to continue? He said no, not really. Though in hindsight going all the way to the Supreme court would have been pretty cool. But one of the main reasons I like Rex so much was that he always listened to me, always worked towards getting me what I wanted. He didn’t have his own agenda to further his career. He really did think of me first. So, we said yes to the offer. I would later find out when she went to them, she more or less read them riot act. That they had screwed up and their arrogance was going to be costly. She told them they had a bulldog at their heels, one who didn’t care about money and couldn’t be bought off. That I was in it for the principal, and they better take our offer or get ready to lose a lot more. They accepted our offer. It was over.

It was a few more months before the settlement money came it. I went to Rex’s office that day for a check. We had agreed to a split that gave Rex $85k and $40k to me. Some folks asked me why I didn’t get more, but I felt that Rex had done the lion’s share of the work and without him I wouldn’t have gotten anything. It wasn’t a life changing sum of money but while I was walking back to my car, I saw a shiny new BMW and thought to myself, I could buy that… But I stashed my check in the bank and moved on.

In the months and years after my case become public, both Rex and I would receive calls asking about the case and asking for advice. They were usually angry photographers who wanted to sue the hell out of someone. My basic advice was to avoid attorneys, to do whatever you could to work something out. That once you get attorneys involved, it is a whole new ball game, and a lot of time and money gets wasted. I just happened to be fortunate that Wyse really screwed up in the way they handled this situation. They should have listened to my concerns. They shouldn’t have run rough shod over my work and then blow me off. They owed me something. And maybe nothing more than a please and thank you and few bucks. But their arrogance cost them.

I would later give a few talks about the case and offer my opinion about copyright issues and things like the term fair use. I would offer up my opinion on the American legal system and how I was fortunate to work with Rex and not the slime ball from New Jersey. But I never got much feedback from my local ASMP community. So, no thank you for doing this, no way to go Mel. Nothing. And yet I maintained my membership in ASMP, as lame as I thought they were. About fifteen years later I had another small issue I wanted legal help on. A stock agency had lost a portfolio of mine as well as those of about 7 other photographers. Back then portfolios were largely hand made and were quite expensive to produce. I called ASMP legal again. A guy named Vic was the man, same guy I spoke to about my lawsuit. I wanted them to just write a letter to the agency and let them know they were being watched. No, nope, we don’t do that. I said that was the second time ASMP had let me down and I was so going quit this lame organization. Second time, he asked. What was the first? I asked him if he was familiar with Curtis vs General Dynamics? He goes oh yea, I use it in my lectures all the time… I said, well I’m Curtis. Big pause. And we didn’t help you? Nope. I said you wouldn’t help me, yet you ride my coat tails. And then Vic says I don’t blame you for quitting. And I did.

The last time I saw Rex was maybe fifteen years ago or so. He had moved to Vashon Island and was slowing down his practice. My career had taken off and I was as busy as ever. We were well into the digital age; the internet age and social media was just starting up. We talked about the case and how things had changed over the years. I asked him if he thought we could win that case now? Without hesitation, he said no, probably not. I am not sure what his reasons were, but I felt the same way. It had become way too easy to steal and no one seemed to care. It’s on the internet, it must be free.

I write this story to preserve my fading memory of the events as they happened. I am sure I have embellished a bit, forgotten a lot, but what I have written is as truthful as a I can recall. If you were to Google Curtis vs General Dynamics, next to nothing comes up. Maybe it is because it happened so long ago. I did find this article.

https://www.owe.com/resources/legalities/27-comping-infringement/

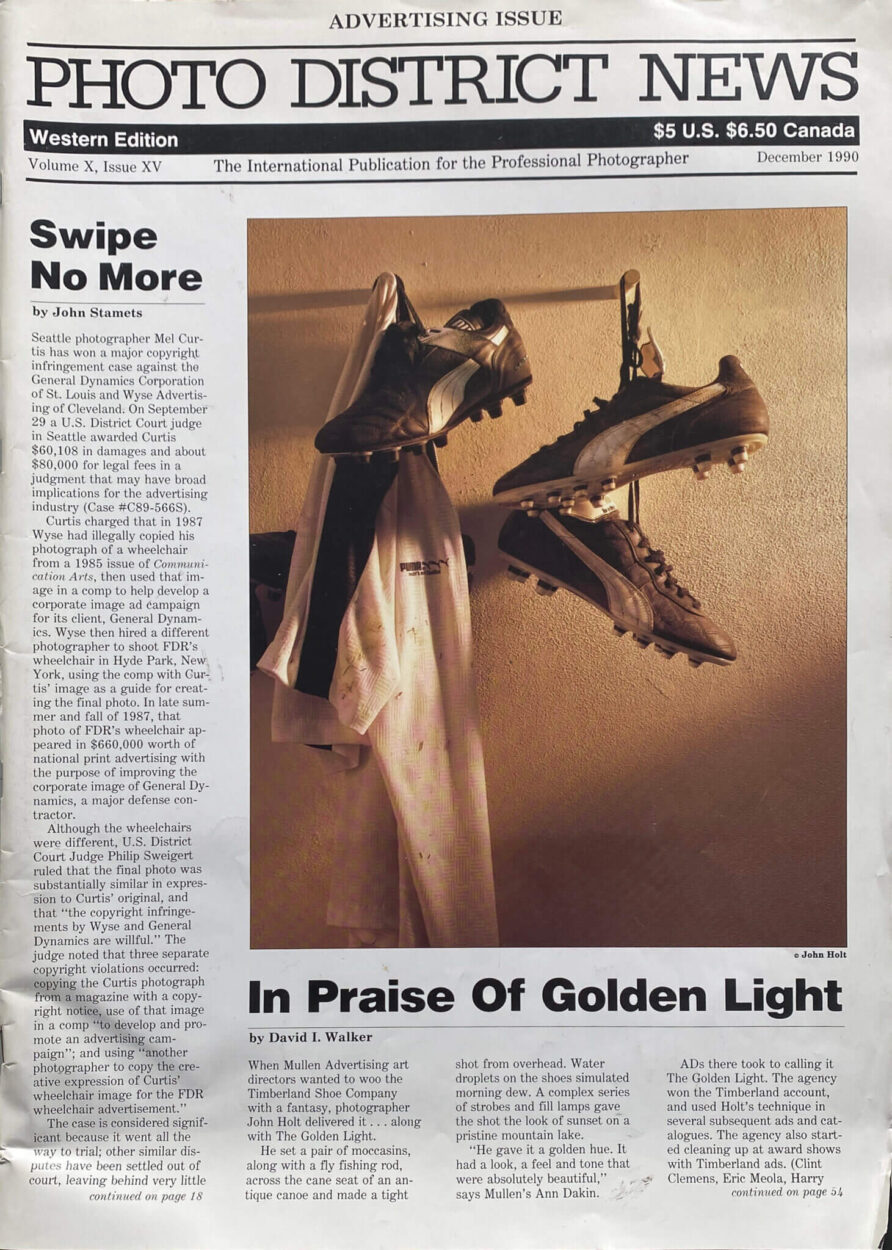

But it only deals with the issue of comping and only references my case. There were two articles written at the time. One by John Stamets Called Swipe No More. It appeared in the December 1990 issue of Photo District News, the prominent photo trade magazine of the time. PDN no longer exists and a request to their archives for a digital link went unanswered. The other article appeared in the local ASMP newsletter in January of 1991. It was written by Gary Hayes. Both writers interviewed me and both articles are well written. John’s article is more in depth and more nuanced, but both are written fairly. To read more, click on the articles below.

I suppose the biggest thing I came away with from my ordeal was an amazing education. I learned all about copyright and intellectual property law and how it applies to an artist such as myself. I learned way more than I ever cared to know about the American Legal system, and how it moves in a glacial, archaic way. This knowledge came in handy many times over the years when clients asked me to copy another artist’s work and I would say that’s not a good idea. The education was extremely handy on my White House project when no one bothered to have me sign a contract, giving away the rights to my work. I learned the meaning of the term precedent and how my efforts would go on to help others in similar situations. And while one might have to dig deep to find anything on the internet about my case, I know it is out there, in some dusty legal journal somewhere. Curtis vs General Dynamics. I will always have that. Unfortunately, I also learned a lot about my industry. For all the talk about community and comradery, I see the world of commercial photography to be pretty cutthroat and every man for himself. That survival and success is less about the quality of your work and more about your ability to navigate the politics. But isn’t that the world in general?